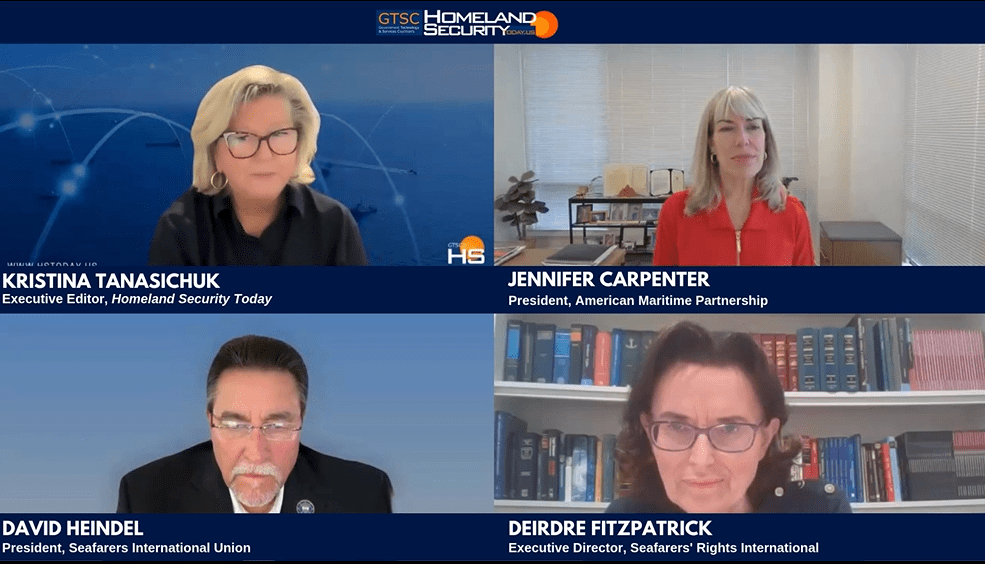

American Maritime Partnership (AMP) President Jennifer Carpenter joined Seafarers International Union (SIU) President David Heinsel and Seafarers Rights International (SRI) Executive Director Deirdre Fitzpatrick joined Homeland Security Today to discuss the value of cabotage laws like the Jones Act to national security. The interview focused on the SRI’s latest report, Cabotage Laws of the World, and what it means for America.

Transcript:

HS Today:

Hello everyone, and welcome to Homeland Security Today. I’m Kristina Tanasichuk, the Executive Editor of HS Today. Today we’re going to dive into a new report from Seafarers’ Rights International called Cabotage Laws of the World. And I know some of you may be wondering, why is HS Today talking about cabotage? But this is one of the most important bodies of law around domestic maritime transportation.

In the U.S., the Jones Act is the policy that governs our domestic maritime transport. It is administered primarily by the U.S. Coast Guard, in collaboration with organizations like CBP, and it is very instrumental to national security and resilience.

Joining me today are three leaders at the forefront of this conversation. First, Deirdre Fitzpatrick, the Executive Director of Seafarers’ Rights International and co-author of the report. Deirdre, welcome.

Deirdre Fitzpatrick:

Thank you very much. Pleased to be here.

HS Today:

And all the way from London — she Zoomed in; see what I did there.

And David Heindel, the President of the Seafarers International Union and Chair of the ITF Seafarers’ Section. Welcome, David.

David Heindel:

Thank you very much. Glad to be here.

HS Today:

And Jennifer Carpenter, the President of the American Maritime Partnership. Thank you all for joining me.

So, I want to start by turning it over to Deirdre to give us some highlights from the Cabotage Laws of the World report, because there are some changes, and they’re interesting given the global state of affairs.

Deirdre Fitzpatrick:

Thank you, Christina. So, cabotage — and specifically maritime cabotage — refers to the practice of reserving a state’s domestic coastal shipping for its own citizens. Cabotage laws restrict how foreign-flagged or foreign-owned, built, or crewed vessels can operate along a state’s coastline or within its maritime zones.

Cabotage has a very long history. Some countries have had cabotage laws for centuries. We’ve been working in this area for about ten years now. When we first looked at historical reports, we found that in 1930, a League of Nations report identified 33 states with cabotage laws.

In 1991, the U.S. Maritime Administration conducted a review to determine whether the U.S. was unique in having cabotage laws. That survey identified 47 such states.

When we published our first edition in 2018, we broadened the review to examine all maritime states globally and identified 91 states with cabotage laws.

We have now updated the report for 2025 and have identified 105 states with cabotage laws. We believe that is a very significant finding. Cabotage has spread globally faster in the past decade than at any point in its history. It exists in every region of the world and across all types of political systems.

HS Today:

Thank you for that overview. For our audience that includes both maritime professionals and the general public, how do cabotage laws enhance a nation’s ability to protect maritime borders and critical infrastructure?

Deirdre Fitzpatrick:

Cabotage laws differ across countries. Each country may define cabotage differently and emphasize different priorities — security, economic policy, workforce development, environmental protection. But fundamentally, countries adopt cabotage laws because they believe doing so is in their national interest. In recent years, geopolitical concerns have increased, and those motivations have become more security-focused.

Jennifer Carpenter:

If I could add to that — sometimes people think only of ocean shipping when they hear “cabotage,” but we’re also talking about who operates on our internal waterways. Thanks to cabotage laws like the Jones Act, when there is a tow moving petrochemicals up or down the Mississippi River, that is a vessel that is American-built, American-owned, and American-crewed. That matters for homeland security and maritime domain awareness.

Christina:

Thank you. So, how does the Jones Act contribute to national defense and strategic sealift?

David Heindel:

The Jones Act ensures that the United States maintains a pool of trained American mariners. In times of emergency — natural disasters, conflict, national crisis — we need mariners to crew U.S. government and commercial vessels that support military operations. Without the Jones Act, the American merchant marine workforce would wither. We’ve seen that happen in places like the United Kingdom and parts of Europe where maritime capacity declined after foreign operators took over coastal shipping. The U.S. has chosen a different path — to maintain a strong merchant marine — and that is essential to national security.

HS Today:

The report shows cabotage laws increasing globally. What trends are driving this?

Deirdre Fitzpatrick:

There is no single reason, but we observed several influences. States look to one another when setting policy, and the documentation of how widespread cabotage has become has influenced new adoption. The post-COVID supply chain crisis led many nations to re-evaluate domestic shipping resilience. Geopolitical tensions have made strategic considerations outweigh pure economic efficiency. And technological developments have expanded cabotage into offshore sectors.

HS Today:

Given these tensions and supply chain threats, what risks do nations face if they weaken cabotage protections?

Jennifer Carptener:

For many years, we have said that the Jones Act allows the U.S. to control its own supply chain. During COVID, we saw foreign-flagged carriers shift capacity to chase profits in global markets, causing major disruptions. But the Jones Act trades remained stable because the operators serving those routes are American companies with long-term commitments to the U.S. If a nation cannot transport essential goods between its own ports, it is vulnerable to coercion or disruption. Thanks to the Jones Act, that is not where we are.

Deirdre Fitzpatrick:

I would just add that our report was written as an objective legal assessment. We are presenting facts. Whether one supports cabotage or not, it is significant that a clear majority of maritime states — 105 out of the world’s coastal states — have chosen to have cabotage laws.

HS Today:

Thank you. We appreciate anyone adding facts to the debate. The Cabotage Laws of the World (2025) report is linked at the end of this webinar and in our summary on HS Today. Thank you all for joining us, and we look forward to continuing this conversation.

Comments are closed.